Posted by Matt Kuhns on Dec 28, 2019

“Kate Warne is one of the most interesting people we know almost nothing about,” Greer Macallister writes in the afterward to Girl in Disguise. I would agree. We know that Warne not only created and led the original “number one ladies’ detective agency” for the intensely demanding Allan Pinkerton, in an era generations before any real advances toward women’s equality; indeed, Warne was so far ahead that Pinkerton’s itself backslid and dispensed with women detectives after she and Allan passed from the scene.

Beyond this, we know some things about Warne’s too-brief professional career, but almost nothing about Warne personally.

Macallister uses fiction to compensate for this shortcoming in Girl in Disguise. I found the exercise well worthwhile.

As a novel, it’s very satisfying. As an attempt to imagine a fully realized person who could have been Mrs. Warne, it’s a success. Some of the other characters are more two-dimensional, but Warne seems like flesh, blood and soul.

A welcome addition to “Great Detectives in Fiction.”

Tags: Kate Warne, other books, Pinkertons

comment (Comments Off on “Girl in Disguise” book)

comment (Comments Off on “Girl in Disguise” book)

Posted by Matt Kuhns on Nov 25, 2019

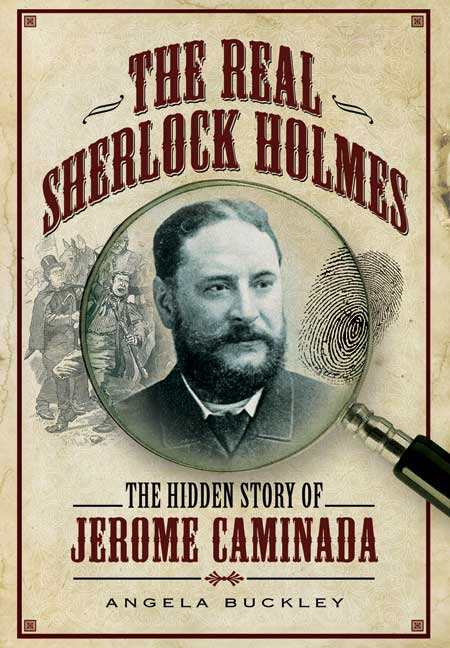

True crime and policework fans may want to check out The Real Sherlock Holmes: The Hidden Story of Jerome Caminada.

Angela Buckley’s 2014 biography of Caminada reviews the full career of a 19th-century Manchester detective, whose accomplishments are certainly worth noting here. I confess that I didn’t find it the most riveting reading, but that’s probably a result of this being familiar territory after my research for Brilliant Deduction, and of being very distracted these days. (I turn a lot to escapist literature and pop nonfiction.)

The title is, I should caution, probably a selling point. Caminada has little direct connection with Sherlock Holmes, and to be honest his career didn’t seem exactly rich with mystery solving either.

But he is a figure well worth this biography, and Buckley deserves credit for researching and telling his story.

Tags: other books, runner-up

comment (Comments Off on The Story of Jerome Caminada)

comment (Comments Off on The Story of Jerome Caminada)

Posted by Matt Kuhns on Nov 28, 2016

I have completed a third book, “officially” released today.

I have completed a third book, “officially” released today.

This is the story of a largely forgotten chapter in the rivalry between Iowa’s two largest universities, the U of Iowa and (my alma mater) Iowa State U. The stars are Iowa president Virgil Hancher, and Iowa State president James Hilton; the plot is their struggle for prestige, resources and influence on the shape of higher education in Iowa during the late 1950s and early 1960s.

The interest, I hope, is a combination of

- alumni & fans’ curiosity about a very different era in what is today mostly an athletics-based rivalry

- meeting the real individuals behind the iconic “Hancher” arts center and “Hilton” college basketball phenomenon

- the intrigue of an administrative political war that made many headlines in its day, but got even more heated in never-before-published memos and other discoveries during my research.

One letter turned up in that research, from University of Rochester president C.W. DeKiewiet to Hancher, summarizes the nature of Hancher vs. Hilton quite well: “Academic men quarrel as readily as men in other sectors of society. Since they persuade themselves more easily that they are standing up for a principle, they can be vigorous and sometimes cruel combatants.”

Read more at mattkuhns.com/hancher-vs-hilton

Tags: other books

comment (Comments Off on My latest book: “Hancher vs. Hilton”)

comment (Comments Off on My latest book: “Hancher vs. Hilton”)

Posted by Matt Kuhns on Aug 6, 2015

I recently acquired a copy of the first major study of one of our heroes since Brilliant Deduction‘s publication. Published just this year, ‘Paddington’ Pollaky Private Detective by Bryan Kesselman is the first dedicated biography of this most mysterious of mystery men. How did he do? How did I do?

Short answer, ‘Paddington’ Pollaky is a stupendous achievement in research. For the Pollaky fan base—which I know does exist, however modest its numbers—this biography is a must. Some of the remarkable nuggets that Kesselman has unearthed are astonishing just for their simple existence:

- Evidence and names of Pollaky’s agents

- An interview with Pollaky

- A photograph of Ignatius Pollaky

Colossal. Add to this extensive correspondence and other archival information, as well as many intriguing new questions which it had not even occurred to ask, before. Was Pollaky’s emigration from Austria-Hungary a flight from political persecution related to the uprisings of 1848? Did he seek—or perhaps even gain—American citizenship before settling in Britain? Was he supplying information to Bismarck’s government in the Franco-Prussian war, thereby earning the German Ritterkreutz?

Read more…

Tags: other books, Pollaky

comment (2)

comment (2)

Posted by Matt Kuhns on Nov 17, 2014

I have written another book, and it’s officially released today! I hope you’ll check out Cotton’s Library: The Many Perils of Preserving History.

Where Brilliant Deduction looked into real detectives who are (now) much less famous than fictional counterparts, Cotton’s Library looks into a priceless historic collection much less famous than individual items within it.

The highlights of this collection include some of the most important documents of Anglophone civilization: the sole manuscript sources of Beowulf and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, two of four surviving 1215 copies of Magna Carta, and the masterfully illuminated Lindisfarne Gospels. The English antiquarian Sir Robert Cotton brought all of these together around 400 years ago, along with thousands of other historic documents.

Yet Cotton and his collection remain relatively little-known despite the renown of many individual items in his library, as well as a story both during and after Sir Robert’s time that almost defies belief. Cotton served time as a prisoner in the Tower of London twice, on dubious charges concealing royal discomfort with the library’s prominence among political critics. King Charles I ordered the library itself locked up in 1629; it remained sealed when its brokenhearted founder expired two years later.

Through the centuries that followed, war, neglect, fires, corrupt library-keepers and later collectors’ poaching all threatened the collection’s ruin repeatedly.

With some tragic exceptions, though, the Cotton library has survived them all. The story of its often narrow escapes is a tribute to unsung heroes of history, beginning with Cotton and continuing into the modern era. Their collective efforts to preserve the library’s great treasures for posterity, set against the sweep of history from Elizabeth I to Elizabeth II, form an epic worthy of James Michener, all of it real.

You can read a free excerpt here. I hope you’ll take a look!

Tags: cotton library, news, other books, other projects

comment (Comments Off on My new book: Cotton’s Library)

comment (Comments Off on My new book: Cotton’s Library)

Posted by Matt Kuhns on Feb 19, 2014

I recently finished Graham Robb’s Parisians: An Adventure History of Paris. A few impressions:

“Files of the Sûreté,” a chapter on Vidocq, was my main motivation in checking this one out. It’s interesting reading. Robb’s portrait of Vidocq is different from my own; some quality of the con artist is nearly indispensable for a confidential agent, but Robb suggests a bit more of the former than I did. One particular vignette within the chapter, “The Case of the Yellow Curtains,” was also of particular interest because I also wrote about the same case in Brilliant Deduction, but Robb focused almost entirely on parts of the story I trimmed out, and vice versa.

Based on his notes, Robb used most of the same sources I did. Being fluent in French, he brought in one or two French works as well as an undoubtedly superior background in French history than I did; on the other hand, I read more widely into the history of detection and was probably better prepared to examine Vidocq within that context. In the end, I didn’t really find any significant incompatibility between the Vidocq in Parisians and my own sketch. The bottom line is that Vidocq was an intentionally chimeric figure. Even within a single account, I think that accurately depicting the “real” Vidocq means recognizing that there wasn’t any single, monolithic “truth” to him. As Robb writes, “So many murky tales are attached to Vidocq’s name that he seems to hover over nineteenth-century Paris like a phantom… The exact truth of these and other tales is almost impossible to separate from the mass of rumour and misinformation.”

For those interested in Vidocq, I think Parisians is largely optional reading, meanwhile. The most notable feature from this perspective is probably in the illustrations, which include a splendid cartoon of Vidocq in his office, drawn by Honoré Daumier in 1836. I had not seen this before, and given that no photos of the great detective are known, publication of any additional image is well worthwhile. Otherwise, though, “Files of the Sûreté” is about 18 pages long, and doesn’t contain much that other sources don’t cover, usually in greater detail. As for the other 370-some pages… I found Parisians very hit-or-miss.

I got through the whole thing, which is more than can be said of Robb’s Discovery of France. Which, it should be said, was critically acclaimed while I’m just some jerk with one self-published book and a blog or two, so one may take or leave my criticisms for whatever they’re worth. That having been said, sometimes Parisians was fantastic, and sometimes it was a slog. Robb approached each chapter with a different, and sometimes wildly different, approach, and while I applaud the spirit of experimentation, I found that many of the individual experiments as well as the whole thing didn’t really work for me. Also, it’s worth noting for anyone else who might care, passive voice is used* with needless frequency throughout the work, and personally I found this a near constant annoyance.

Again, though, grammatical choices aside, this included some excellent chapters, and in all honesty there are a lot of histories of Paris already; trying something different is going to involve risk… which in this instance I don’t think paid off very well… but if you aren’t trying something different, writing yet another Paris history is probably not an especially worthwhile exercise in the first place.

* This is me making a joke.

Tags: Graham Robb, other books, Vidocq

comment (Comments Off on Vidocq among the Parisians)

comment (Comments Off on Vidocq among the Parisians)

Posted by Matt Kuhns on Jul 10, 2013

I recently finished reading Daniel Stashower’s recent work The Hour of Peril, about Allan Pinkerton and the “Baltimore Plot” against Lincoln. I quite enjoyed his examination of the murder of Mary Rogers in The Beautiful Cigar Girl, and was naturally intrigued by this new title; I’m happy to report that The Hour of Peril exceeded my expectations. Having gone over much of the same territory in my own research, I wasn’t certain how much I would be able to get out of the book but Stashower included an impressive amount of new detail, and not only on the Baltimore Plot. I was surprised and fascinated at how much was new to me about Pinkerton’s early life and first cases; admittedly it’s been a couple of years since I read them, but I made notes on the major studies of Allan Pinkerton and I’m certain that a number of points in The Hour of Peril were absent from all three. On that basis, alone, I can heartily recommend this new volume to anyone interested in learning more about the Pinkertons’ founder.

I recently finished reading Daniel Stashower’s recent work The Hour of Peril, about Allan Pinkerton and the “Baltimore Plot” against Lincoln. I quite enjoyed his examination of the murder of Mary Rogers in The Beautiful Cigar Girl, and was naturally intrigued by this new title; I’m happy to report that The Hour of Peril exceeded my expectations. Having gone over much of the same territory in my own research, I wasn’t certain how much I would be able to get out of the book but Stashower included an impressive amount of new detail, and not only on the Baltimore Plot. I was surprised and fascinated at how much was new to me about Pinkerton’s early life and first cases; admittedly it’s been a couple of years since I read them, but I made notes on the major studies of Allan Pinkerton and I’m certain that a number of points in The Hour of Peril were absent from all three. On that basis, alone, I can heartily recommend this new volume to anyone interested in learning more about the Pinkertons’ founder.

It’s also, as advertised, a tightly paced but very detailed examination of “The Secret Plot to Murder Lincoln Before the Civil War,” i.e. the Baltimore Plot.

The general outline of events in The Hour of Peril does, I found with some relief, essentially match up with the very condensed version in Brilliant Deduction. But this expanded account was well worth reading (and not only for Stashower’s effort at restoring a little bit of life to the figure of Kate Warne, commendable as that was). It provides much food for thought about how to interpret the much-debated questions of both the Plot, itself, and Allan Pinkerton’s service to his adopted country in the Civil War.

Read more…

Tags: Allan Pinkerton, Baltimore plot, Civil War, other books

comment (Comments Off on Allan Pinkerton’s Civil War reputation)

comment (Comments Off on Allan Pinkerton’s Civil War reputation)

Posted by Matt Kuhns on Jul 8, 2013

I probably should have done this a while ago. But, better late than never; the other day it occurred to me to post suggested “further reading” about Brilliant Deduction‘s protagonists in fiction. Nearly all of them have inspired some sort of fictional tales, after all, either of themselves or of close analogues.

Vidocq probably leads the list, in every way. His own influential Memoirs are, most likely, at least semi-fictionalized. According to one rumor, in fact, they were mostly the work of his friend Honoré de Balzac, who definitely wrote other fictionalized works inspired by Vidocq. Father Goriot, Lost illusions, and Scenes from a Courtesan’s Life are all available for free in English translation at Project Gutenberg. The same is true of multiple stories of Emile Gaboriau’s detective Lecoq: The Lerouge Case, The Mystery of Orcival, File No. 113, and Monsieur Lecoq. (Et aussi Les Esclaves des Paris, si vous connaissez le français). And, while it may stretch things a bit, it might be worth mentioning Les Miserables if only because Vidocq may have contributed inspiration to both of its main characters…

The Road child murder case investigated by Jonathan Whicher has inspired more than one work of fiction, though to my knowledge Wilkie Collins’s The Moonstone is the only one to include any significant analogue to Whicher himself (as Sergeant Cuff). Inspector Bucket of Bleak House, whose author Charles Dickens knew Whicher personally, may actually bear more resemblance to Whicher, though. (Even if JW’s colleague Frederick Field was the “official” model for the character.)

I suspect that most of the Pinkerton dynasty’s outings in fiction have taken inspiration from Allan, rather than his children; the only exception I know of is the graphic novel Detective 27, which gives a little space to William though Allan still gets most of the best scenes. Brief searching, meanwhile, also turns up Pinkerton’s Secret: A Novel and Nevermore – a novel of Edgar Allan Poe and Allan Pinkerton.

Read more…

Tags: Balzac, comics, Dickens, fiction, other books, Pollaky, Whicher

comment (Comments Off on Further reading in fiction)

comment (Comments Off on Further reading in fiction)

Posted by Matt Kuhns on Jun 26, 2013

The professional detective is primarily an urban figure. I touch on this association a few times in Brilliant Deduction, as well as how the rise of the detective profession to its greatest prominence coincided with the rise of the expanding industrial cities of 19th century Europe and America; the combination of very large concentrations of people (mostly unfamiliar to one another and constantly being joined by immigrants from the countryside or overseas), with evolutions in commerce (e.g. the spread of banking services) and transportation (e.g. the railroad’s enabling rapid access to distant points on the map) found old-fashioned law enforcement measures sorely wanting.

I was pleased to see some of the same ideas, recently, examined in a work looking at the other side of the phenomenon, i.e. cities. In City: A Guidebook for the Urban Age, P.D. Smith considers seemingly more aspects of life than not, in fact, appropriately enough given his thesis that the tendency toward urban life is an essential part of what defines the human race. At any rate, a great deal of human experience since the beginning of recorded history has been part of the urban experience, certainly, crime and crimefighting being no exceptions.

Smith notes that “Crime fiction emerges at the same time as the rise of the great industrial cities of Europe and America,” including detective fiction, the prototype of which was Poe’s “The Murders in the Rue Morgue.”

When “The Murders in the Rue Morgue” was first published, the word “detective” did not even exist in the English language. The first detective department [in the Anglophone world] appeared the year after, in 1842. Even in 1840, New York… had no full-time, professional police force. Indeed, there was little serious crime. But over the coming decades the situation changed as the city grew rapidly. In 1859, the New York Herald complained: “Our record of crime to-day is truly appalling. Scarcely is the excitement attending one murder allayed when a fresh tragedy equally horrible takes place.” … Within thirty years, policing became New York City’s single largest expenditure and there was a growing fear of organised crime.”

Pretty much, yeah. Poe, of course, was partly inspired to write the first detective story by the exploits of the first detective, Vidocq… the word “detective” was introduced to the English language by Charles Dickens, in articles about Jonathan Whicher and other members of the detective force established to address London’s “appalling” crime problems… in the years ahead, the rapid growth of not only New York but newer American cities on the western frontier, such as Chicago and San Francisco, created opportunities for remarkable figures in both private detection (such as Allan Pinkerton) and public forces (such as Isaiah Lees). Even the one exception to Brilliant Deduction‘s otherwise urban-dwelling cast, Ellis Parker, may have lived and worked in a rural small-town setting but was at the same time firmly within the super-urbanized region that first spawned the term “megalopolis.”

One might indeed have subtitled my book The Story of Real-Life Great-City Detectives… except that it would have been thoroughly redundant.

Tags: cities, fiction, other books, P.D. Smith

comment (Comments Off on Detection and The City)

comment (Comments Off on Detection and The City)

Posted by Matt Kuhns on Apr 23, 2013

A few notes on the interesting work I finished, recently, Butch Cassidy: Beyond the Grave by W.C. Jameson.

Butch and his partner Sundance (who was probably not his closest friend or partner-in-crime, as Mr. Jameson observes in the process of brushing aside the many endearing myths about the pair) receive the briefest, one-line aside mention in Brilliant Deduction. But the Pinkertons’ interest in the pair was considerably more enduring (and indeed, as said aside notes, more enduring than that of their financier clients who were content to drop pursuit of the pair once they left the country). Thus they turn up repeatedly in the pages of Butch Cassidy, or at least their files do; William, Robert and a few agents appear in person now and then, but for the most part the Pinkertons are simply an agency, hovering in the background and compiling notes in preparation for a reckoning that never came.

Those files make, or contribute to, interesting reading a century later. Jameson writes that

During the time of the so-called shootout in San Vicente [the one dramatized in the much-loved film with Newman and Redford], the Pinkertons probably knew more about the location and activities of Cassidy and Harry Longabaugh [i.e. Sundance] than anyone. A thorough search of the files of the Pinkerton National Detective Agency yields no information to suggest that they ever believed Butch Cassidy had been killed in San Vicente.

As much as I love the 1969 movie, and its iconic ending, Jameson makes a compelling case that the Pinkertons’ skepticism about the banditos yanquis‘ alleged demise was warranted, too.

Read more…

Tags: Butch Cassidy, other books, Pinkertons, Tichborne Claimant

comment (Comments Off on Butch Cassidy, beyond the grave?)

comment (Comments Off on Butch Cassidy, beyond the grave?)

comment

comment